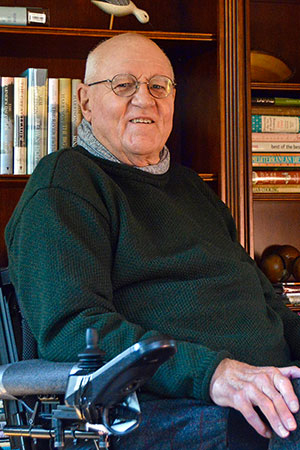

NDLA Board honors Vietnam veteran John Lancaster ’67, ’74 J.D. for contributions to disability rights

John Lancaster ’67, ’74 J.D., a Vietnam War veteran and pioneering advocate for disability rights, was honored this spring with the Notre Dame Law Association’s Father William Lewers Award.

Judge Thomas D. Schroeder ’84 J.D., president of the NDLA Board, presented the award to Lancaster at the board’s spring meeting on March 24 in recognition of his “distinguished service to the United States, his contributions to people with disabilities worldwide, and his life’s reflection of Notre Dame values.”

The citation on the award also included the observation that “Lancaster’s story reminds us that some of our most committed peacemakers are warfighters.”

Lancaster was nominated for the award by two retired Marines, First Sgt. Jim Barnett and Lt. Col. Patrick J. Finneran Jr. ’67, ’09 Ph.D. (Hon.). Lancaster and Finneran both attended the University of Notre Dame on Navy ROTC scholarships and graduated in the same class. Barnett was the assistant Marine officer instructor for the Navy ROTC unit at Notre Dame when he first got to know Lancaster and, a Vietnam combat veteran himself, has stayed in close touch with him ever since.

“John is truly an American hero in war and in peace. His combat injuries led him to becoming a national leader for civil and human rights for people with disabilities,” Finneran said. “His love for Notre Dame, and her values have been a guiding force in his life. He has the admiration and respect of all who know him. It was sincerely a privilege for me and Jim Barnett to recommend John for this wonderful award.”

Lancaster graduated from Notre Dame as a second lieutenant in the Marine Corps. After further training, he was deployed to Vietnam in January 1968, where at the age of 23 he found himself in command of a platoon of 18-year-old Marines in the midst of the bloody Tet Offensive.

In the early morning hours of May 5, 1968, Lancaster’s men bore the brunt of a sudden night-time attack by an overwhelming force of combined Viet Cong and North Vietnamese Regulars. Upon hearing one of his wounded men cry out for help in the darkness, Lancaster determined to reach him and ran forward into the enemy fire to engage in hand-to-hand combat until bullets ripped open his chest, punctured both of his lungs and shattered his spine. Fellow Marines were able to take the lieutenant back to a medical triage area where he received lifesaving treatment from Corpsman Donald “Doc” Whistler.

After the dust settled from the hours-long battle, it was discovered that 18 of the 32 men in Lancaster’s platoon had been wounded and four had been killed.

Sgt. Gary Jarvis served with Lancaster during the battle. His 1999 book, “Young Blood: A History of the 1st Battalion, 27th Marines,” described Lancaster’s heroism in this way:

Rather than order one of his men to risk being shot or killed, the lieutenant unselfishly risked his own life to aid the Marines in his platoon. If it were not for 2d Lt. Lancaster’s actions, other Marines probably would not be alive today. Two Marines had simultaneously gone out to help the wounded Marines, but it was the courageous lieutenant who paid the price. Never has there been a lieutenant more brave and committed to his men.

For his part, Lancaster recalls that he lived only because “a really good corpsman figured out which lung he could plug up. He rolled me onto my side to let me breathe, gave me something to hold onto and warned me that to survive I had to resist the shock, stay conscious, and not let myself roll onto my back.”

Lancaster was awarded the Bronze Star with Combat V in recognition of his heroism in the face of great personal hazard.

He was now a disabled war veteran who no longer had the use of his legs.

Becoming an advocate

Speaking by video at the NDLA’s award ceremony, Lancaster noted that he completed his long hospital rehabilitation only to discover that his country’s lack of accessible facilities meant that he could no longer board a bus, a train, or even most airplanes. It stung to be denied even the simplest pleasures such as going to a restaurant with his family. Most buildings — including government buildings — were inaccessible to him.

During a 1970 meeting with a Notre Dame Law School associate dean to discuss his application, Lancaster was warned that, like most buildings in the country at the time, the Law School’s 1930 building was not designed with wheelchairs in mind. At that time, there were no ramps to exterior entrances, no student bathrooms on the classroom floor, and no public elevator to other floors within the building. Moreover, the first-year class was already full; no more seats were available. Lancaster replied with a firm, “You do not need to worry. I will get into the building the same way I got in today, and I will bring my own seat.” Lancaster attributes his admission to then-Dean William B. Lawless Jr.

Barnett said a lot of people in Lancaster’s position might have just sat back, drawn their government disability retirement, and lived out the rest of their life.

“This was not something that John was going to do,” Barnett said. “He decided to go back to Notre Dame, buy a house, go to law school, and find things in life where he could make a difference. John has been able to accomplish all these things and more.”

The national accessibility picture had not improved when Lancaster passed the bar exam and began the practice of law. At times he found the barriers infuriating.

“When you can’t get on a city bus — and your taxes are helping to pay for that bus — you start getting a little cranky,” Lancaster said. “When you can’t get up a courthouse’s steps, especially when you’re an attorney, you start getting a little cranky.”

Testifying before the U.S. Senate Foreign Relations Committee in 2012 in support of the ratification of the International Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, Lancaster said, “The employment discrimination I experienced as a young attorney was unbelievable. The only ones who would hire me were the VA’s Board of Veterans Appeals.”

Lancaster’s life changed when two disability advocates invited him to join them as a lawyer for the Paralyzed Veterans of America. There he found his calling, helping to draft cutting-edge federal and Maryland laws protecting the legal rights of people with disabilities.

His innovative work brought him to the attention of the White House, where he worked with both the George H.W. Bush and Clinton administrations to implement the Americans With Disabilities Act — the historic 1990 civil rights law that protects people with disabilities from discrimination in many areas of public life. Lancaster toured all 50 states to explain the new law to businesses, rehabilitation services, and people with disabilities — including many veterans.

In the fall of 2000, Lancaster was invited to the Notre Dame-Air Force football game to receive the Rev. William Corby, C.S.C., Award in recognition of his distinguished military service.

Lancaster and Barnett, who had nominated Lancaster for the Corby Award, sat together in the press box during the game. At one point, Lancaster turned and asked what Barnett would think of him going back to Vietnam to help disabled Vietnamese veterans fight for their accessibility rights. After a moment, Barnett looked at Lancaster and said, “If you feel you need to go back there to do that, you have my blessing.”

Return to Vietnam

Lancaster spent 2000 to 2004 working in Hanoi as an advisor to the Vietnamese government on disability law, policy, and programs — a project funded by the U.S. Agency for International Development.

Professor Emerita Patricia O’Hara, who graduated with Lancaster in the Law School’s Class of 1974, noted in her remarks at the NDLA award ceremony that she found Lancaster’s return to Vietnam to be a particularly powerful chapter in his life.

“A Vietnamese-American came to his office and asked if he would be willing to help Vietnamese veterans — which meant helping primarily North Vietnamese veterans. John returned to Vietnam to do just that, becoming close friends with a person he describes as a disabled Vietnamese veteran who adapted a motorcycle with a third seat on the back so that John could ride with him,” O’Hara said. “Although the two men had served on opposite sides during the Tet Offensive, they worked together to bring to Vietnam the same changes for the disabled that were happening in the United States.”

Lancaster explained that his friend was Manh Tuan, a North Vietnamese soldier who had suffered the same type of paralyzing injury that Lancaster suffered, and in the same battle — but by an American bullet.

After Lancaster returned from Vietnam for the second time, he went on to serve in leadership positions with Humanity & Inclusion, the President’s Committee on Employment of People with Disabilities, the United States International Council on Disabilities, the U.S. Institute of Peace, and the National Council for Independent Living.

Rev. William Lewers, C.S.C., joined the Notre Dame Law School faculty in 1965 and became director of the Center for Civil and Human Rights in 1988. The award is presented by the NDLA to a Notre Dame Lawyer who has devoted outstanding service in the area of civil and human rights or worked for social justice.

In her remarks, O’Hara recounted that she once asked Father Lewers why he converted to Catholicism. He replied jokingly that, “I converted because I believed in Catholic social justice teaching; once I converted, I found out that I was the only one who did!”

O’Hara concluded her remarks by addressing Lancaster directly.

“The Class of 1974 has many successful members. We have people who rose to judicial positions, as well as people who served as managing partners of their firms to name but a few. But I think it is safe to say that there is no member of our class of whom we are prouder than you, John,” she said.

“Thank you for the breadth of your heart, the acuity of your mind, and the courage and strength that allows us to claim you as a graduate,” O’Hara said. “I think that if I asked Father Bill now why he converted, he would say, ‘Because I believe in Catholic social justice teaching — and thank God I’m not the only one who does.’”

The photos on this page were used with permission from the U.S. Institute for Peace, which published a feature story on John Lancaster in 2020. Read “A Vietnam Veteran’s Fight — for Dignity and Peace.”