Notre Dame Religious Liberty Clinic represents Sikhs, Muslims, Bruderhof, and Jewish groups defending a Rastafarian inmate forcibly shaved bald

Notre Dame, IN — A Rastafarian man was forcibly restrained and shaved completely bald in violation of his religious beliefs while being held in a Louisiana correctional facility. His case underscores the importance of religious freedom laws being interpreted to provide sufficient remedies to protect the rights of religious minority groups in prison.

The Notre Dame Religious Liberty Clinic filed an amicus brief in the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals case Landor v. Louisiana Department of Corrections and Public Safety yesterday, representing Bruderhof, Sikh, Muslim, and Jewish groups. The brief asserts that monetary damages should be considered “appropriate relief” under the Religious Land Use and Institutionalized Persons Act (RLUIPA). In Landor, plaintiff Damon Landor, a devout Rastafarian, had his religious rights stripped away by state officials when he was forced to cut his dreadlocks in violation of his sincerely held religious beliefs. Landor has since been released from prison and is seeking monetary damages against the state officials who threatened his religious rights.

Religious Liberty Clinic Legal Fellow Francesca Matozzo stated, “This case provides a particularly egregious example of why injunctive relief is not enough to ensure that prisons respect the religious rights of their detainees. The Fifth Circuit has already told the Louisiana prison system that its grooming policy violates RLUIPA. And yet, without the ability to seek money for this wrong, Landor would be left without any recourse to hold the prison accountable for its actions.”

Landor v. Louisiana Department of Corrections and Public Safety

Click on the link above to read the case documents that Notre Dame Law School’s Religious Liberty Clinic filed in the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit.

Landor was incarcerated in the summer of 2020. He had been growing his dreadlocks for 20 years after taking the Nazarite vow of separation, an ancient biblical oath which commands the Nazarite to let their hair grow long in dedication to the Lord. During his first five months of incarceration he was held at two facilities—St. Tammany Parish Detention Center and LaSalle Correctional Center—both of which allowed him to keep his dreadlocks as an expression of his faith.

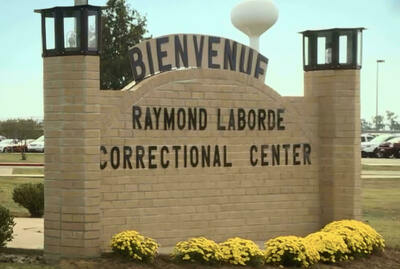

On December 28, 2020, three weeks before his release date, Landor was transferred to the Raymond Laborde Correctional Center. Despite explaining that he was a Rastafarian and that his dreadlocks constituted a protected form of religious expression; furnishing several federal and state forms establishing his right to a religious accommodation; and handing the guard a copy of the Fifth Circuit’s decision in a previous case which held that the Department of Corrections’ grooming policy against dreadlocks violates RLUIPA when applied to devout Rastafarians, Landor alleges that the officer conducting Landor’s intake interview ordered him to be handcuffed to a chair, forcibly restrained, and shaved completely bald.

Landor alleges that he was subjected to further punishment after this incident of physical and spiritual humiliation; he was placed in lockdown, where he remained for the next three weeks until his release on January 20, 2021. Each day that he was in lockdown, Landor requested a grievance form so that he could file a complaint. The prison refused.

The Clinic’s brief makes a case for the importance of providing robust relief to vulnerable religious minorities in prison.

Stephanie Barclay, director of Notre Dame’s Religious Liberty Initiative said, “Religious minorities disproportionately suffer restrictions on their religious exercise. Prisons have less incentive to adjust non-accommodating policies or update trainings to address minority faiths because they may rarely detain a prisoner of that faith. The failure to do so causes religious minorities to be subject to infringements that majority religions do not face. At worst, these groups may face hostility, skepticism, or discrimination because their practices are less well-known.”

“To be sure,” she continued, “prisons are not expected to have comprehensive knowledge of every minority religious practice. But they must take seriously requests for religious accommodation rather than relying on ignorance to deny minorities their ability to practice.”

The amicus brief was filed on behalf of the Sikh Coalition, a nonprofit organization dedicated to ensuring that members of the Sikh community are able to practice their faith; Bruderhof Communities, an intentional community of Christians who suffered persecution for their conscientious objection in Nazi Germany; the Jewish Coalition for Religious Liberty (JCRL), a nondenominational organization of Jewish communal and lay leaders who seek to protect the ability of all Americans to freely practice their faith; and CLEAR (“Creating Law Enforcement Accountability and Responsibility”), a project at City University of New York School of Law that protects Muslim and all other communities in the New York City area that are targeted by law enforcement under the guise of national security and counterterrorism.

“Infringement of free exercise of faith through sincere religious practices is a particular concern for people of small or less known faith groups. This fundamental right applies to all and is too precious to be protected only for powerful majorities. That's why we count on courts to hold officials to account,” said John Huleatt, General Counsel at the Bruderhof.

“It is common sense as a matter of textual interpretation that the Religious Land Use and Institutionalized Person Act should be interpreted to allow for monetary damages just like its sister statute the Religious Freedom Restoration Act,” added Howard Slugh, General Counsel at JCRL.

“We appreciate this opportunity to inform the Fifth Circuit why this case is important to religious minorities in general and Jewish Americans in particular. We are very proud to do so alongside a religiously diverse coalition of our friends and neighbors. The Jewish Coalition for Religious Liberty could not function if it were not for the generosity and incredible work of our friends and allies. We are extremely grateful to the Notre Dame Religious Liberty Initiative for ensuring that our voice would be heard on this important issue,” Slough concluded.

Notre Dame students Jared Huber and Athanasius Sirilla contributed to the brief alongside Matozzo and Barclay.

“The opportunity to play a role in ensuring that the rights of even minority religions are protected is why I came to law school,” said Huber, a 2L in his first year of work with the Clinic. “Mr. Landor’s case presents an incredible way to be involved in furthering religious liberty protections by arguing that egregious violations of religious beliefs or practices should have an appropriate remedy. While working on this brief, I was surprised to learn of the vast unawareness of minority religious practices in prisons and of the strategies they employ to avoid remedying religious violations. I hope Mr. Landor’s case serves to reduce wrongs like the one he experienced.”

Landor v. Louisiana Department of Corrections and Public Safety is the third case taken up by the Religious Liberty Clinic this fall in which it defends the right of incarcerated minorities to freely practice their faith. Read more about the Clinic’s work in Emad v. Dodge County and Walker v. Baldwin.

About the Notre Dame Law School Religious Liberty Initiative

Established in 2020, the Notre Dame Law School Religious Liberty Initiative promotes and defends religious freedom for all people through advocacy, formation, and thought-leadership. The initiative protects the freedom of individuals to hold religious beliefs as well as their right to exercise and express those beliefs and to live according to them.

The Religious Liberty Clinic has represented individuals and organizations from an array of faith traditions to defend the right to religious worship, to preserve sacred lands from destruction, to promote the freedom to select religious ministers, and to prevent discrimination against religious schools and families.

Learn more about the Religious Liberty Initiative at religiousliberty.nd.edu.