Experiencing freedom after 30 years on death row

“You never think about freedom until it is taken away from you.”

Emotional and raw, Anthony Ray Hinton told his story to an overflowing crowd of law students, undergraduate students, and community members at Notre Dame Law School’s McCartan Courtroom on Tuesday.

Walter Jean-Jacques, a second-year law student who serves as the vice president of the Notre Dame Exoneration Project, was instrumental in bringing Hinton to the Law School for this student-led event. "This past summer, I was an Equal Justice America Fellow and Nationals Lawyers Guild-Haywood Burns Fellow at the NAACP Legal Defense Fund. During one of my assignments, I was able to meet Mr. Hinton and hear him speak. I knew I had to invite him to come and share his story at Notre Dame."

Hinton spent 30 years on Alabama’s death row for crimes he didn't commit. He talked about his wrongful conviction, his decades in prison, and the lingering effects he has experienced after leaving prison.

He left Notre Dame Law students with a challenge to serve justice.

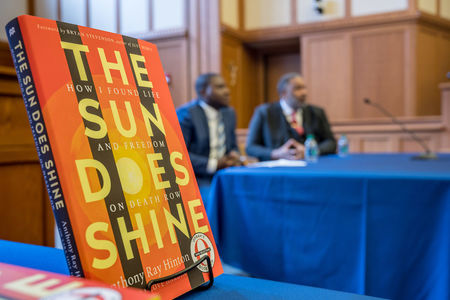

Anthony Ray Hinton speaks to students on November 13, 2018, in the Patrick F. McCartan Courtroom at Notre Dame Law School. (Photos by Matt Cashore)

Anthony Ray Hinton speaks to students on November 13, 2018, in the Patrick F. McCartan Courtroom at Notre Dame Law School. (Photos by Matt Cashore)

In a booming voice he asked the audience, “How is it that we have a system that allows an innocent man, regardless of race, creed, or color, to spend 30 years in prison for a crime he didn’t commit?”

Hinton described an Alabama judicial system rampant with racism and injustice, a system with no concern about whether someone was wrongfully incarcerated. And he blames that system for his 30 years on death row.

In 1985, he was convicted of murdering two restaurant managers near Birmingham, Ala. The only evidence linking him to the crimes was the testimony of state lab technicians, who said that the bullets from the crime scene came from a revolver found in his mother’s home.

“I wish I could look you in the eye and tell you that the state of Alabama made a mistake and that race had nothing to do with it. But Alabama did not make a mistake. Race had everything to do with me spending 30 years in a five-by-seven cell,” he said.

He recalled an ordinary hot July day that would lead to three decades of “pure hell.” He had been enjoying lemonade with his mom and making plans to attend a church revival that evening. Then, as he was cutting the grass, two Birmingham detectives showed up and arrested him. With no idea of why he was being arrested, the detectives asked Hinton if he or his mother owned a firearm. He told them his mother owned a firearm, which they later retrieved from his home.

He says people always ask him why he told the police about a gun they had no knowledge of. “My mother taught me to tell the truth. If you have done nothing wrong, there is no reason to lie. So, I told the truth,” he said.

'You will be convicted'

Hinton repeatedly asked police why he was being arrested. Eventually he was informed that he was being charged with first-degree robbery, kidnapping, and attempted murder of a third restaurant manager who had survived and identified Hinton from a photo. He maintained his innocence, telling the detectives that he was at work during the time the incident took place. His supervisor confirmed this fact, providing an alibi.

Hinton shared shocking details about conversations he had with police during his arrest, further illustrating a state judicial system where racial issues were still a significant problem in the 1980s. According to Hinton, the detectives told him that they did not care whether Hinton did the crime or not, but that they intended to make sure that Hinton was found guilty.

“One of the detectives said, ‘You will be convicted because you are black, a white man said you shot him, and you will have a white prosecutor, a white judge, and a white jury,’” said Hinton.

Later, the detectives said they would instead be charging him for the murders of the two other restaurant managers. Hinton said that the detectives did not actually believe he had committed the new crimes. He said they told him, “I should take this rap for one of my home boys.” Hinton said he had tears coming down his cheeks when he told them, “There is not a home boy in this world I would take a rap like this for.”

Hinton was assigned a public defender who had no faith in his innocence and who hired an inexperienced ballistics witness to testify for him. He was convicted and sentenced to death row. He was 29 years old.

For three years Hinton did not speak to anyone. He soon realized in order to survive he would have to escape into his imagination. He created a world where he and the Queen of England would drink tea and talk about the royal family. He described with a chuckle how he married Halle Berry, who was the perfect wife according to Hinton, always saying “yes” or “okay, dear” and never spending any money. He later left Berry for Sandra Bullock.

Through cell bars he eventually made friends with other death row inmates. Fifty-four inmates were executed while he was on death row. He read a lot and started a book club, all while steadfastly maintaining his innocence.

For years, his appeals were denied. He added a bit of humor, when he described working with a pro bono lawyer from Boston for a few years. At first, he was not sure he could work alongside him because Hinton, a beloved New York Yankee fan, was not sure he could do anything alongside a Boston Red Sox fan. Hinton laughed and said, “I put that aside.” However, serious philosophical differences got in the way. The lawyer suggested pursuing life without parole rather than a death sentence, but he would have to admit to committing the crime.

“While I appreciated his work on the case, life without parole is for guilty people. I could never plead guilty to a crime I did not commit. If Alabama wanted to execute me for a crime I didn’t do, then let them. I would never say I did it,” he said.

'God sent me his best lawyer'

In 2002, Bryan Stevenson of the Equal Justice Initiative (EJI) took up his case. Stevenson is the founder and executive director of the organization. Hinton and Stevenson agreed on a strategy to focus on the murder weapon. For years, Hinton’s lawyers questioned whether the bullets could be conclusively linked to the weapon. Subsequent tests raised doubts about whether the weapon in Hinton’s home had fired the bullets — and even whether the bullets were all fired from the same gun.

Hinton knew that race would still be a factor in his case. “I told Stevenson that he had to hire a qualified ballistic expert with certain qualifications. I told him that the expert had to be a white male from the South. He must believe in the death penalty, and be the very best. But above all, he needed to tell the truth.”

Hinton asked, “What type of justice do we have that color makes a difference in who helps you and who doesn’t?”

EJI introduced evidence from three gun examiners who concluded that the gun could not be matched with the ballistic evidence. However, the state court of Alabama still did not re-examine the case. In 2014, the U.S. Supreme Court, responding to an appeal from a lower court, ruled that Hinton’s constitutional right to a fair trial had been violated and that Hinton should receive a new trial. A year later, a judge dismissed the charges against him. On April 3, 2015, Hinton left death row a free man.

Hinton credits Stevenson, saying, “God sent me his best lawyer.”

He spoke frankly to the students in the room and asked them to think about several questions.

“Who would you be if they came for you? What would you do if you were charged with a crime you didn’t commit? What would you do if you didn’t have the money to hire a decent attorney? What would you do if you passed a polygraph test, but they cared more about the color of your skin than the merits of the case? What would you do if you were found guilty and sentenced to die? Who would you be? What would you do if you had to spend every day in a cell the size of your bathroom? What would you do after 30 long years, waiting to die, and you were finally set free? Who would you be?

“Every day I have to ask myself, ‘Who am I?’ Because I know for a fact that I am not the 29-year-old that went in and spent 30 years in a five-by-seven cell.”

The aftermath of life in prison affects him every day. He has fixed up his mother’s home, where he now lives. She died while he was in prison. His nights are still not normal. He thought he would be able to stretch out in the California king size bed he bought, but three years later he still sleeps in a fetal position like he had to in prison. He still wakes up at 3 a.m., because that is what time he ate breakfast in prison. And, even though he can shower whenever he wants now, he still only showers every other day.

Addressing law students, he said, “For those of you here becoming lawyers, I do not have a problem with you becoming a prosecutor. I have a problem if you lie. I have a problem if you knowingly send innocent men and women to be slaughtered like animals.”

Hinton said, “Believe in justice. Never cheat and not seek justice. I am a broken man, and I ask you to pray for me and for those who are innocent on death row. The system you believe in is badly faulted.”

He left them with a challenge to become lawyers for the right reasons, saying that we need young people to stand up for justice. “You are going to inherit something that can only be fixed. I want you to become a great lawyer, a great prosecutor, but never sell yourself out.”

After the talk, Hinton met with attendees and signed copies of his book, The Sun Does Shine: How I Found Life and Freedom on Death Row. His talk was sponsored by the Notre Dame Exoneration Project, in collaboration with the American Constitution Society, Federalist Society, and Klau Center for Civil and Human Rights.